BY RON GREEN JR.

Let’s take a moment and close our eyes, maybe pour a taste of a favorite libation to warm the soul, and consider what could have been.

What if Donald Ross had never come to Pinehurst?

What if Ross had never met a Harvard astronomy professor named Robert Wilson who convinced him to leave his native Scotland where he had learned golf and all that goes with it from Old Tom Morris and come to Boston in 1899?

What if Ross had never met James Walker Tufts a year later in Boston and been convinced to hop a train south and spend his winters in the North Carolina sandhills with its therapeutic air and sandy soil begging to be transformed into golf courses, fulfilling a corner of Tufts’ dream that he had not fully imagined?

Imagine a Pinehurst built on croquet and tennis more than golf.

At Pinehurst, we're fortunate to celebrate Donald Ross everyday. But today, on the 150th anniversary of his birth, we are especially proud to commemorate his lasting legacy at the Cradle of American Golf.

We'll have much more today and in the coming days to celebrate Ross. pic.twitter.com/Hq5zumSKig

— Pinehurst Resort (@PinehurstResort) November 23, 2022

The world is full of what ifs but there is only one Pinehurst and there was only one Donald Ross and whether it was fate, fortune or a higher power that could see what was possible, Ross and Pinehurst found each other.

On the occasion of what would have been Ross’s 150th birthday, the spirit of Ross is as alive as ever in Pinehurst, the great man’s vision, principles and imprint enduring like an eternal flame in the village he called home.

“Without Donald Ross there is no Pinehurst,” says course designer Gil Hanse, who reimagined Pinehurst No. 4 while also creating The Cradle and Thistle Dhu. “It’s deeper than that. He imbued Pinehurst with the soul, the Scottish knowledge of what golf can be. It’s critical to why Pinehurst is so special to all of us.”

On the pages of an atlas or in the results of a Google search, Pinehurst is a place located near the middle of North Carolina, possessing an abundance of small town charm while also coping with its share of challenges, not unlike other towns along the way.

What separates Pinehurst is what Ross created, not by himself, and it has a rare presence. It is more than a place. Pinehurst is a feeling, a state of mind, a living, breathing example of what the best of us can create and share with a touch of divine inspiration.

What Ross and Tufts literally dug out of the sandy soil more than a century ago has been nurtured by citizens, caretakers and visionaries who have been wise enough to look to the future while keeping one eye on the past. Pinehurst isn’t timeless but it is a place where yesterday, today and tomorrow exist shoulder to shoulder, tied together by the words and deeds of a Scottish immigrant who saw the value in what golf could be.

“He is the Old Tom Morris of American golf,” says author Chris Buie, who wrote ‘The Life & Times Of Donald Ross.’

Like Morris, who is still celebrated in St. Andrews where his great granddaughter still lives above the shop he had just off the 18th green of the Old Course, Ross was a transformative figure. Ross didn’t just design nearly 400 golf courses including many in the Pinehurst region, he elevated the game on a national level.

Near the turn of the century, golf was becoming popular but the people who played it and did business in the game did not rank high on the social ladder of the day. When Ross, the son of a mason, made his first trip to the United States he was a listed as ‘servant’ on his census card.

“When I was a young man in Scotland, I read about America and the American businessman absorbed in making money. I knew the day would come when the American businessman would relax and want some game to play, and I knew that game would be golf,” Ross wrote in his book ‘Golf Has Never Failed Me.’.

“I read about the start of golf in the United States, and knew there would be a great future in it, so I learned all I could about the game: teaching, playing, club-making, greenkeeping and course construction. And then I came to America to grow up with a game in which I had complete confidence. Golf has never failed me.”

The 9th hole of No. 2 remains one of the iconic course’s toughest.

What Ross brought with him from Scotland – and what largely defines Pinehurst today – is a gift for understanding how golf courses and the land fit with one another. Born a short walk from Royal Dornoch Golf Club where he was introduced to the game, Ross saw how that classic links looked and played as if the course had been there at the creation.

At the Old Course and Carnoustie and other spots throughout Scotland, Ross was surrounded not only by design brilliance but immersed in a culture that valued golf not just for the shot making but also for the sense of community and its culture.

Ross has been gone since April 26, 1948 when he died of a heart attack not far from his masterpiece, Pinehurst No. 2, but his influence has lived on.

“Pinehurst is like St. Andrews, it has the same template,” Buie says. “(Ross) presided over the club like a paternal presence.

“He was like the Henry Ford of golf. The game became part of the shining city on the hill idea, every place had to have a golf course. No one did more to establish the game.”

At Pinehurst, Ross was the golf pro, a clubmaker and the club manager. Sift through the Tufts Archives and there are folders full of correspondence from Ross, much of it dealing with club business matters such as laundry and upkeep of the buildings.

A strong player himself – Ross once led the Open Championship in the third round until those scores were wiped out because not every player finished that day – his impact on the North & South Open became a template of sorts for the Masters when it began in 1934. Ross made sure the players were treated well and including special touches such as flowers on bedside tables for their wives.

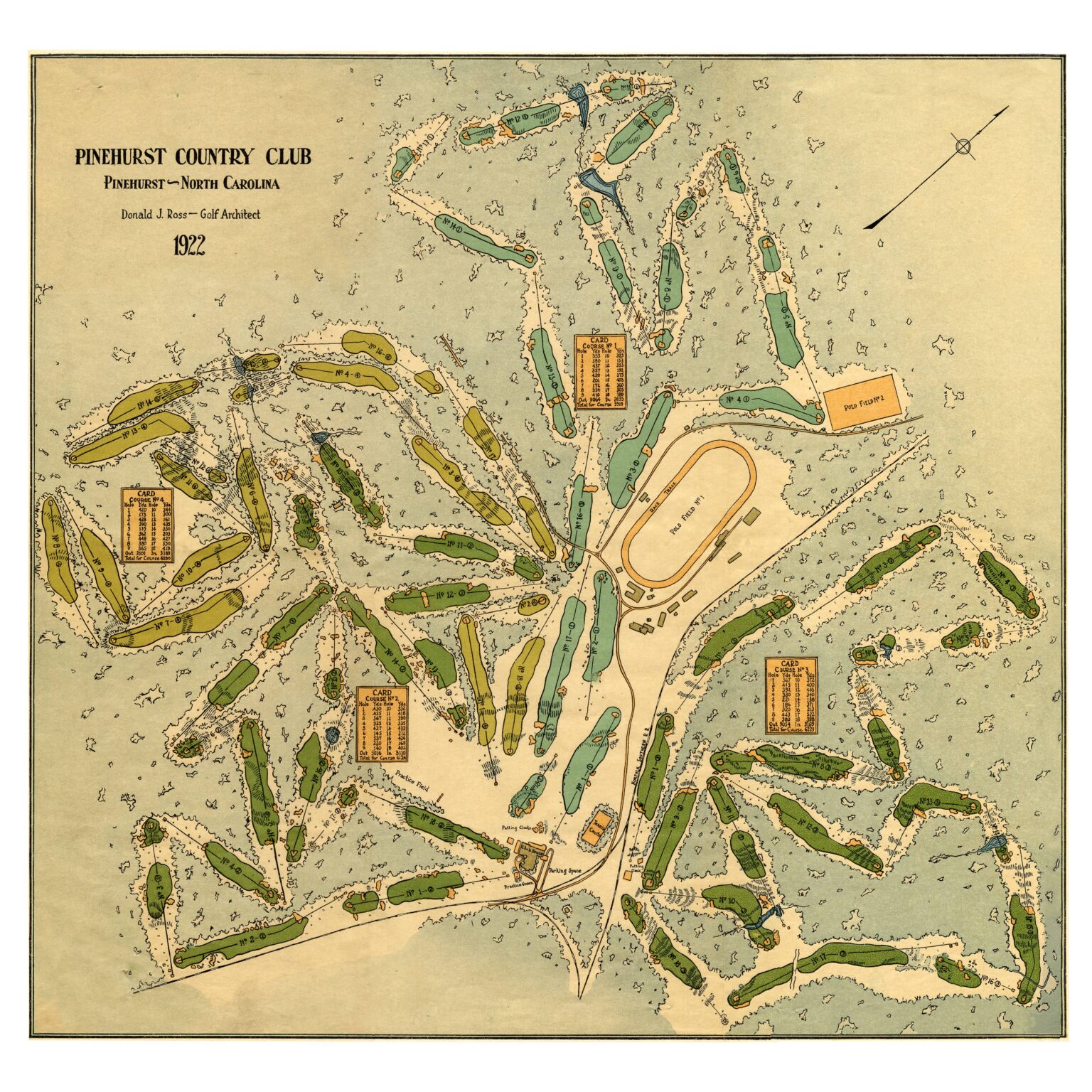

In the Tufts Archives are volumes of drawings Ross did, detailing the golf courses he designed. He traveled by train and was often away for weeks at a time, allowing him to put on paper what he was putting on the ground.

He did his work before bulldozers were available to push dirt around, effectively using what the ground gave him. Not all of his courses featured turtle back greens like No. 2. From Seminole to Oakland Hills, Scioto to Wannamoisett, Ross designs could be as different as they were distant from one another.

As Buie puts it, Ross could “build a hole within a hole, a course within a course.”

Ross worked from a core of fundamental beliefs, such as:

- “A course that continually offers problems – one with fight in it, if you please – is the one that keeps the player keen for the game.”

- “Make each hole present a different problem. So arrange it that every stroke must be made with a full concentration and attention necessary to good golf. Build each hole in such a manner that it wastes none of the ground at my disposal, and takes advantage of every possibility I can see.”

- “Don’t let famous holes like those or many others, such as the Alps of Prestwick and Redan of North Berwick, lead you into attempting to reproduce them. In trying to make your course fit certain famous hole treatments, you are certain to be doomed to disappointment. Make your holes fit your course. No other way can be satisfactory.”

Like most artists, Ross’s work developed over time. Course No. 2 opened in 1907 and wasn’t completed until Ross built the fourth and fifth holes in 1935. Along the way, the third, sixth and seventh holes were redesigned.

Living in a house on Midland Road that backs up to the third green at No. 2, Ross was never far from his most precious design, the one Jack Nicklaus has said repeatedly is his favorite in the world from a design standpoint.

Step inside what is now called the Dornoch Cottage where Ross and his second wife, Florence Blackenton spent their fall and winter months, and it is easy to imagine him there. He cultivated roses, azaleas and 13 different types of holly trees in his back yard where he could glance up and watch golfers going past.

The house has a spacious den that looks over the back yard and toward the course and there are photographs of Ross and his wife in their high-backed chairs reading in front of the fireplace.

Donald Ross’s office in Dornoch Cottage today.

His small office has been kept much as it was when Ross worked there. It’s compact with a drawing table and chair pushed against the front wall. There is a story that Ross liked to keep a light burning in his office in the evening so passersby would think he was working even if he wasn’t there.

“It seemed almost like he was the mayor of Pinehurst,” says Hanse, who lived in Dornoch Cottage while doing his work at No. 4 and The Cradle.

At times, Ross lamented how much work he did but it made him a wealthy man. He bought the Pine Crest Inn with a friend in 1920. In 1924-25, Ross received a salary of $6,500 from Pinehurst and he made approximately 10 times that with his course design work.

Some years Ross would be involved in the building of 20 to 30 courses and he had approximately 3,000 people working for him, making him a captain of sorts in an industry he helped create.

Through it all, he kept coming back to Pinehurst. He loved the northeast where he spent his summers in Rhode Island, still tied near the place where he originally landed from Scotland in his 20s.

Pinehurst, however, has a pull like few places. With Tufts’ vision and the artistry of Frederick Law Olmstead, who designed the Pinehurst village without ever setting foot there, it was born with a head start.

It was Ross, a proper Scot who could project a stern bearing that masked a sharp sense of humor, who brought it all together.

Someone else could have built golf courses in Pinehurst a century ago but that’s likely all they would have been – golf courses.

Ross built more than that. He built a place where golf lives, where church bells ring on the hour and where life has a different cadence.

Some call it the spirit of Pinehurst.

It may be Ross’s greatest creation.